Diplomacy has a pretty clear set of priorities. It doesn’t really matter what order we consider them in but they are: survive, draw, win. Most players will enter a game with the aim of winning, gaining that illusive solo. At some point in the game, the objective may change to preventing another player from winning – surviving to be part of a draw. At the beginning of a game, while the win is kept in mind, many players will simply look to survive the early mêlées.

Well, in theory, anyway. When I say “most players”, I am leaving aside those strange and wearisome players who enter a game of Dip aiming to draw. I’m also leaving aside tournament play, in which it may be more profitable to scramble after SCs (thanks to tourney scoring systems being poor representations of how to play Dip ‘normally’) or because it may be more profitable to earn a draw from a given game.

However, what happens when you come across that player who assigns herself the role of the Armoured Duck or, as I more comfortably know it, the Kingmaker? This player comes to the point in her play where she decides she is going to throw the game to an opponent, effectively giving up on the usual priorities. She isn’t going to win; she isn’t interested or believes she can’t gain a draw; she is so pissed off with one opponent that she decides to give another opponent a chance at soloing.

The Armoured Duck

I’m not sure whether Richard Sharp was the originator of the phrase but in his book The Game of Diplomacy he uses the term: ‘There is one type of player who infuriates me beyond measure, the one I think of as the Armoured Duck.’1 Here, the reference is to a player who ‘Isn’t up to the cynical skills of [Diplomacy].’ Why? Because he is hell-bent on revenge.

This isn’t necessarily the same as a Kingmaker, but it was likened to kingmaking in a topic raised on Playdiplomacy.com’s forum. This topic was titled A Treatise on Kingmaking, written by a player (known by the username ‘ruffdove’) and aimed to discuss what Kingmaking is and when – or if – it was ever acceptable.2 In this topic another member (‘Chumbles’) posted: ‘In olden days, a Kingmaker would be called an Armoured Duck.’

If we accept Sharp’s definition of the Armoured Duck, such a player might be a Kingmaker but he might just be a stubborn, vengeful player who is also interested in achieving as good a result as possible.

The Kingmaker

In contrast, the Kingmaker isn’t interested in achieving anything other than helping an opponent win. She will attack her target, or defend herself from her aggressor, relentlessly, not being interested in achieving a result. She’s decided that she’s going to throw the game to the beneficiary of her so-called strategy.

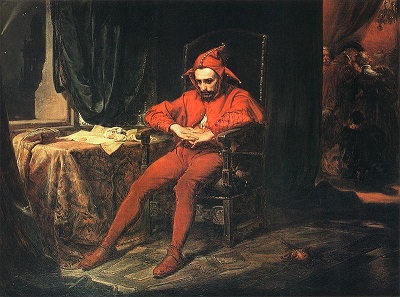

While both the Armoured Duck and the Kingmaker have vengeance in mind, the Kingmaker is seen by many players as detestable. She provides for no possible room for negotiations; she has no goal left in the game except suicide. She is, in short, a villain of the highest rank.

Or is she..?

Kingmaking as a Strategy

In his post, ruffdove specified that kingmaking could only be called ‘kingmaking’ if it has the goal of presenting the beneficiary with the chance to win outright. However, the strategy is valid in other situations.

We’ve all come across that player – possibly that Armoured Duck! – who just doesn’t see sense… well, as far as we’re concerned, anyway. He keeps up his attack on us and so presents another player with the opportunity of winning, whether this is because he doesn’t recognise the impact his blind assault is having on the game or because he simply doesn’t care. Perhaps he is allied with a player who is zeroing-in on a solo and genuinely believes he has a shot at a 2-way draw.

Whatever the motivation, the player simply doesn’t see SENSE! So you try to wake him up. You warn him that he needs to change tack; you point out the strategic implications… yet he continues.

What are you left with? Perhaps you’re left with making a threat along the lines of: “Look, keep this up and Italy is going to win anyway. I can’t help stop him if I’m having to defend against you. So unless you stop and look at what’s happening – and DO something about it – I’ll give the game to Italy.”

Now, you’re left with a dilemma: Do you follow through with the threat or do you prove yourself a coward and keep plodding along? Do you act as the villain, throwing the game, or do you try to stick to the principles in which you pride yourself – keep working to prevent a solo?

Assuming you aren’t a coward, you have little choice. You withdraw all forces from your border with the player for whom you’re now effectively playing, throw everything at the ‘fool’ who has forced you into this position and – perhaps – hope that the latter will finally do something.

And if he doesn’t? Well, the pathway is clear: you become a Kingmaker.

Whether one agrees with this strategy, whether one believes it is a ‘proper’ strategy or not, it is certainly a valid one. If one player is being idiotic, if you can see no way around it, there’s not much else you can do, certainly having set the train in motion. Whether you intended it or not, the locomotive heads down the track to the end of the line and crashes through your principles. You may have hoped that the outcome would be different but that’s the risk you take.

As a strategy, threatening to act as Kingmaker may be valid. What a principled player will aim for is that this acts like an adrenalin shot to the game, forcing the player who is being ridiculously stubborn in his assault on you to find a way to keep the game alive by changing his tactics.

That isn’t always how kingmaking is employed, however.

Villainy

There are some players out there, lurking in the dark corners of the Hobby, who don’t believe in the same principles of Diplomacy. Some are there to win and – if they don’t win – they resort to vengeance against the player who prevented that win. If they aren’t going to win and you effectively ended their game then they are going to help someone else win… just because. Some may not be as win-only focused as this but they react to a stab simply by destroying the stabber’s game.

This is extremely frustrating, as Sharp says. As the target of the Kingmaker, you’re left with no way of rebuilding an alliance with the Kingmaker. You’re drawn into a hopeless situation: the solo draws ever closer and, with you involved in a war of attrition, you can’t do anything to prevent it.

Kingmakers can ruin games. All the effort you put into it comes to naught. Every player remaining in the game is left with one outcome or the other: defeat, or – if you are the beneficiary of the kingmaking – victory. The losers feel cheated with one exception: the Kingmaker himself, who sits back and grins. “OK, it’s a loss but damn that felt good.” The victor feels that the win was cheaply gained and this takes the gloss off it.

But, is this a true reflection of the game? Who is – are – the real villain(s)?

Kingmaking as an act is, occasionally, not something a victim could do anything about. Occasionally, the Kingmaker is simply that kind of person. Often, however, this isn’t the case. Often, the Kingmaker feels there was no real alternative. She’s on the runaway train. In that situation, the other players should ask themselves what caused the game to reach this inglorious conclusion.

The Sob Story

“I was a victim of kingmaking. John was a complete idiot. He simply wouldn’t change his mind and was unapproachable. I tried to warn him but all he wanted to do was throw the game.”

Perhaps. Perhaps not.

The point about kingmaking, as another member of the Playdip forum pointed out (‘Crunkus’), is that a player has to reach the point of acting as a Kingmaker. In reaching this point, and going beyond it, what had motivated this decision? There is only one answer: the actions and/or words of the other players in the game.

This isn’t always the case, as I’ve said above. Sometimes a player simply has the mind-set that, if you stab him, he’ll throw the game – or try to. That player should be run out of a game as soon as possible. Reputation-building cuts both ways. However, let’s leave this player aside and focus on the player who genuinely reaches the point where kingmaking seems to be the only way to go. Why did John act as a Kingmaker?

There are a number of potential answers to this question. I’m not going to try to be exhaustive here but let’s look at three of them: personality, communication, and strategy.

Personality

Diplomacy is a game about relationships. You work at building a good relationship with players. You want them to help you win, which is against their interests. You don’t achieve this by being obnoxious.

There is no ‘right’ way to approach Diplomacy. Your style might be forceful, helpful, demanding, accommodating, chatty, business-like, honest, deceitful, etc. Whatever works for you. Personally, I think being flexible is best, adapting the way you approach players to match the circumstances and to match their style.

What is a solid generalization, however, is that rudeness and bullying aren’t going to work in the long-term. If you’re one of those players who throws abuse around like a farmer muck-spreading, you’re going to come out smelling like you’ve rolled in it. If you are constantly demanding in your negotiations, you’re going to wear out another player’s patience. If you use a stick consistently, the animal is going to turn on you.

A player who is the recipient of this kind of ‘diplomacy’ may well work with you initially while her interests match yours. That’s sensible. However, whether you stab her or not, she’s going to grow tired of the approach. And, when the situation reaches a head, you are likely to find yourself left high and dry. Why should she put up with an obnoxious player?

Simply put, if you’re a bastard then expect others to play in a way that damages you. Is this what caused the kingmaking?

Communication

In a way, I’ve covered one aspect of this above. While you’re negotiating, rudeness isn’t going to lay smooth roads. It isn’t going to lay up treasure in a heavenly alliance.

Another aspect is whether you maintain effective communications. Not necessarily highly strategic communications, but whether you communicate at all and the consistency of your communications.

There was a study of what causes betrayal, based upon Diplomacy.3 Surprisingly – to me, at least – it concluded that players who focus on future strategy too greatly were likely to be betrayed. So watch out for this – but this is a little aside! As far as kingmaking goes, you should consider how you communicate. Does the subject of your communications put a player off? If you only concentrate on strategy – whilst this may seem reasonable – this may make you seem less ‘likable’.

Perhaps more importantly, if you’ve stabbed a player, do you give up on communicating? What about if you’ve been stabbed? Alternatively, do you reach out?

The point I’m trying to make is that a player who tries to communicate is a player who should be able to maintain some sort of relationship. You might not think there’s much to talk about: either you stabbed your opponent and that’s that or you were stabbed so, “Bugger off, Mr Stabber.”

Now, what about that other player, the one the Kingmaker gives his support to? What has she been doing? Yep, she’s been keeping communications going. Perhaps she even stabbed the Kingmaker earlier in the game but made some sort of an effort. I’m not necessarily saying she sent those poor “So sorry…” messages but she kept the lines of communication open. In contrast, you couldn’t be bothered. You couldn’t find anything to say; you let yourself fall into the trap of not wanting to make the effort any more.

Strategy

Finally, I want to consider how the situation in the game affects whether a player decides to go down the kingmaking track.

Were you relentless? Did you keep up an attack to the point that the Kingmaker simply had no room to hope for an alternative to total annihilation? If so, then you allowed him no room to move.

Were you one of the other players, not necessarily directly involved with the situation which led to the act of kingmaking? What did you do to prevent it? Did you recognise what was happening and apply pressure on other parties? Did you carry on, hoping something would happen to change the course of the game but that this ‘something’ would come from someone else?

Foolhardy Heroes

Being a hero – here, sticking to the principles of the game no matter what and simply despising the Kingmaker – can be as much a contribution to the decision of the Kingmaker as anything else.

It isn’t enough to simply decry the act of kingmaking. Like it or not, what a player chooses to do with his units, how a player chooses to play a game, is up to him. Others can sit back in high-minded judgement and bemoan the state of the Hobby or the act of the player if they want. Better, though, to examine what might have led to the act.

It isn’t enough to shout at a player who is acting as a Kingmaker in a game. The chances are she knows exactly what she’s doing. In general (although there are certainly a fair number of examples to question this!) Dip players aren’t stupid. Treating her as if she is will only exacerbating the situation.

We should accept that kingmaking is something that can be prevented and that it should have been preventable. This isn’t always be the case, certainly, but often it is. Instead of shining the light of shame on the Kingmaker, stand under the beam yourself.

Who is the real villain of the piece?

References:

- Richard Sharp, The Game of Diplomacy, Chapter 2.

- ruffdove, A Treatise on Kingmaking, Playdiplomacy.com Forum.

- Vlad Niculae, Srijan Kumar, et al, Linguistic Harbingers of Betrayal: A Case Study on Online Diplomacy.

|

Rick Leeds (playdip.com.notice@gmail.com) |

If you wish to e-mail feedback on this article to the author, and clicking on the envelope above does not work for you, feel free to use the "Dear DP..." mail interface.