A simple recursive guess algorithm that works in all cases

When I was writing the DATC, I had contact with a few people who were developing an adjudicator. One of them was Christian Hagenah, the creator of DipTool. He explained to me that DipTool does not work with decisions based on partial information.

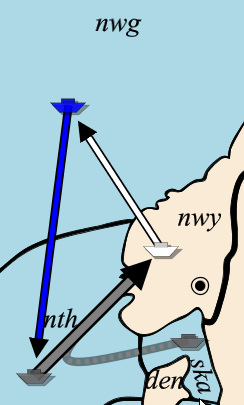

Again we look at the circular movement with one supported move:

|

England: F nwg -> nth Germany: F ska Supports F nth -> nwy F nth -> nwy Russia: F nwy -> nwg |

What we can do (as alternative for a decision based on partial information) is to make a guess for one of the units in the cycle. For instance, we could guess that the English fleet in the Norwegian Sea succeeds. After this guess, the Russian in Norway can advance and so does the German fleet in the North Sea. Now, we recalculate the guess. Since the German fleet left the North Sea, the English fleet is free to move there. This means that the resolution of the English fleet equals our initial guess. Thus, we have a consistent resolution.

However, there might be a second resolution. So we also evaluate with the guess that the English fleet fails. As consequence, the fleet in Norway will bounce, but the German fleet in the North Sea will still advance, due to support from Skagerrak. Again, we recalculate the guess. Since, the North Sea is open, the fleet in the Norwegian Sea will advance. This contradicts the guess that the adjudication is based on. Thus, this is an inconsistent resolution.

Of the two guesses, only one led to a consistent result. So we just choose the resolution where the English fleet succeeds in moving. If the unit in Skagerrak is removed, then both guesses will lead to a consistent resolution, and the situation has to be passed to the backup rule.

DipTool builds up an explicit directed graph based on the dependencies of the orders. These are the same type of graphs as drawn in the previous chapter in figures 11, 12, 13, 14 and 15. The algorithm starts to work on the nodes that do not have any outgoing arrows. Those are the orders that are not dependent on any other order. It resolves those orders first, and removes them from the graph. Orders that do have dependencies will get rid of their outgoing arrows at the moment that all dependencies are resolved. When there are no longer any nodes with outgoing arrows, this means either that all orders are resolved, or that there is a cyclic dependency. For the cyclic dependency, it will use the guessing approach.

Both times that the order of the German fleet in the North Sea was resolved, the resolution of the Russian order was known. Although this information was based on a guess, the function that executes the equation does not need to know this. This shows the advantage of the guess algorithm above an algorithm that makes decisions based on partial information. All information for calculating a equation is available, and this avoids having to program the equations twice, which would be required for the partial-information based algorithm.

There are also some disadvantages. First of all, it was not invented by me! More seriously, this method requires additional software for graphs and to set up these graphs. For languages such as Java, standard graph libraries are probably available; but for a language like C, this requires significant coding.

So it would be great to combine the advantages of the different approaches, by using guesses to avoid double-coding for decisions that must be based on partial information, but also avoiding large amounts of generic code.

At first I couldn't figure it out, but a few years later, when the problem popped up in my head again, I finally got it. And as always with these kind of things, when you look back, you wonder why you didn't find the solution earlier.

The algorithm cannot handle orders that are part of multiple cycles: but that doesn't matter, because according to theorem I, such multiple cycles cannot exist. For a badly defined variant rule, such orders might exist, and the graphs of DipTool or partial information decisions might be easier to adapt. In the standard game, however, multiple cycles simply do not exist.

I give here a part of the algorithm in C. It successfully passes tests for circular movement, convoy paradoxes, and cyclic dependent situations with only one resolution. For readers who cannot read C, I will explain what is going on afterwards:

1 /* Possible resolutions of an order. */

2 #define FAILS 0

3 #define SUCCEEDS 1

4

5 /* For each order we maintain the resolution. */

6 int resolution[34];

7

8 /* The resolution of an order, can be in three states. */

9 #define UNRESOLVED 0 /* Order is not yet resolved, the

10 * resolution has no meaningful

11 * value.

12 */

13 #define GUESSING 1 /* The resolution contains a value,

14 * but it is only a guess.

15 */

16 #define RESOLVED 2 /* The resolution contains a value,

17 * and is final.

18 */

19 int state[34];

20

21 /* A dependency list is maintained, when a cycle is

22 * detected. It is initially empty.

23 */

24 int dep_list[34];

25 int nr_of_dep = 0;

26

27 /* Function: resolve(nr)

28 * nr - The number of the order to be resolved.

29 * Returns the resolution for that order.

30 */

31 int resolve(int nr) {

32 int i, old_nr_of_dep, first_result, second_result;

33

34 /* If order is already resolved, just return

35 * the resolution.

36 */

37 if (state[nr] == RESOLVED)

38 return resolution[nr];

39

40 if (state[nr] == GUESSING) {

41 /* Order is in guess state. Add the order

42 * nr to the dependencies list, if it isn't

43 * there yet and return the guess.

44 */

45 i = 0;

46 while (i < nr_of_dep)

47 if (dep_list[i++] == nr)

48 return resolution[nr];

49 /* Order not found, add it. */

50 dep_list[nr_of_dep++] = nr;

51 return resolution[nr];

52 }

53 /* Remember how big the dependency list is before we

54 * enter recursion.

55 */

56 old_nr_of_dep = nr_of_dep;

57

58 /* Set order in guess state. */

59 resolution[nr] = FAILS;

60 state[nr] = GUESSING;

61

62 /* Adjudicate order. */

63 first_result = adjudicate(nr);

64

65 if (nr_of_dep == old_nr_of_dep) {

66 /* No orders were added to the dependency list.

67 * This means that the result is not dependent

68 * on a guess.

69 */

70

71 /* Set the resolution (ignoring the initial

72 * guess). The order may already have the state

73 * RESOLVED, due to the backup rule, acting

74 * outside the cycle.

75 */

76 if (state[nr] != RESOLVED) {

77 resolution[nr] = first_result;

78 state[nr] = RESOLVED;

79 }

80 return first_result;

81 }

82

83 if (dep_list[old_nr_of_dep] != nr) {

84 /* The order is dependent on a guess, but not our

85 * own guess, because it would be the first

86 * dependency added. Add to dependency list,

87 * update result, but state remains guessing

88 */

89 dep_list[nr_of_dep++] = nr;

90 resolution[nr] = first_result;

91 return first_result;

92 }

93 /* Result is dependent on our own guess. Set all

94 * orders in dependency list to UNRESOLVED and reset

95 * dependency list.

96 */

97 while (nr_of_dep > old_nr_of_dep)

98 state[dep_list[--nr_of_dep]] = UNRESOLVED;

99

100 /* Do the other guess. */

101 resolution[nr] = SUCCEEDS;

102 state[nr] = GUESSING;

103

104 /* Adjudicate with the other guess. */

105 second_result = adjudicate(nr);

106

107 if (first_result == second_result) {

108 /* Although there is a cycle, there is only

109 * one resolution. Cleanup dependency list first.

110 */

111 while (nr_of_dep > old_nr_of_dep)

112 state[dep_list[--nr_of_dep]] = UNRESOLVED;

113 /* Now set the final result and return. */

114 resolution[nr] = first_result;

115 state[nr] = RESOLVED;

116 return first_result;

117 }

118 /* There are two or no resolutions for the cycle.

119 * Pass dependencies to the backup rule.

120 * These are dependencies with index in range

121 * [old_nr_of_dep, nr_of_dep - 1]

122 * The backup_rule, should clean up the dependency

123 * list (setting nr_of_dep to old_nr_of_dep). Any

124 * order in the dependency list that is not set to

125 * RESOLVED should be set to UNRESOLVED.

126 */

127 backup_rule(old_nr_of_dep);

128

129 /* The backup_rule may not have resolved all

130 * orders in the cycle. For instance, the

131 * Szykman rule, will not resolve the orders

132 * of the moves attacking the convoys. To deal

133 * with this, we start all over again.

134 */

135 return resolve(nr);

136 }

The programmer should write an adjudicate function that implements all the equations. This function should not update any global data, and if it needs to know whether a move, support or convoy order succeeds or fails, it should call the resolve function (instead of looking in the global data). The resolve function may return a result based on a guess, but that is of no concern of the adjudicate function. So, the adjudicate function does not know anything about the state of an order, while the resolve function does not know anything about the equations.

To finalize the program, the programmer should implement the backup_rule function, and implement a main function that sets all orders to UNRESOLVED at the beginning of adjudication and then calls the resolve function for every order.

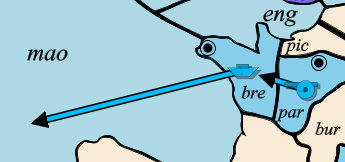

In cases where there is no cyclic dependency, the algorithm behaves similarly to the simple recursive algorithm (without guessing) as described earlier in this article. Consider the simple situation of figure 8:

|

France: A par -> bre F bre -> mao |

If the resolve function is called for the Paris order, then the recursion is as follows:

resolve(par)

adjudicate(par)

resolve(bre)

adjudicate(bre)

return SUCCEEDS (for adjudicate(bre))

return SUCCEEDS (for resolve(bre))

return SUCCEEDS (for adjudicate(par))

return SUCCEEDS (for resolve(par))

The only difference from the simple recursive algorithm (without guessing) is that the resolve(par) call will put the Paris order into a GUESSING state with the resolution FAILS (line 58 to 60), before calling adjudicate(par).

However, when the adjudicate(par) function returns with a positive result, the resolve function will notice that the adjudication result is not dependent on any guess (line 65). The initial GUESSING state is just ignored and the Paris order is set in a RESOLVED state with resolution SUCCEEDS.

The GUESSING state becomes relevant in case of a cyclic dependency:

|

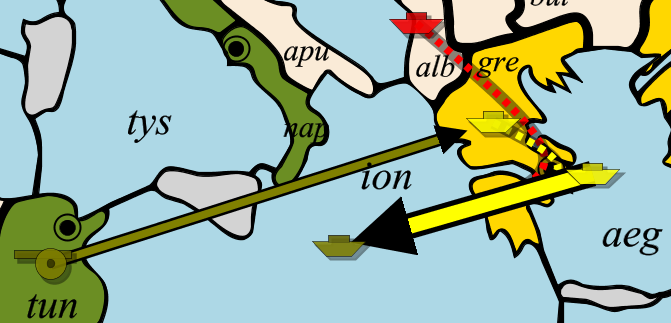

Turkey: F aeg -> ion F gre Supports F aeg -> ion Austria: F alb Supports F aeg -> ion Italy: A tun -> gre F ion Convoys A tun -> gre |

If we could make decisions based on partial information, then we could conclude that the fleet in the Aegean Sea has an attack strength of at least 2 and maybe as much as 3, depending on the support of Greece. The strength of 2 is enough to advance to the Ionian Sea. With this guessing algorithm such a conclusion is not possible anymore, because the adjudicate function needs full information (although the function is not aware of whether the information is final or a guess).

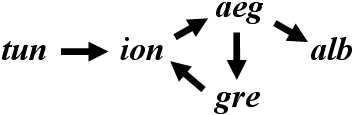

Suppose we call the resolve function for one of the orders in the paradox, for instance resolve(aeg). How the recursion will develop, will become more clear if we look at the dependency graph:

Recursion will enter in the direction of the arrows, alternating between the resolve function and the adjudicate function:

resolve(aeg)

adjudicate(aeg)

resolve(alb)

adjudicate(alb)

return SUCCEEDS (for adjudicate(alb))

return SUCCEEDS (for resolve(alb))

resolve(gre)

adjudicate(gre)

resolve(ion)

adjudicate(ion)

resolve(aeg)

In this case, it is assumed that adjudicate(aeg) will first call resolve(alb) and then resolve(gre). This will lead to an early RESOLVED state for Albania, because this order is not dependent on any other order. If resolve(gre) is called as first, then the Albanian order will be resolved when recursion as result of resolve(gre) has unwinded.

Along the way, the resolve function will set the state of the orders to GUESSING (line 60) and with an initial guess FAILS (line 59).

| Order | State | Resolution |

|---|---|---|

| F aeg -> ion | GUESSING | FAILS |

| F gre Supports F aeg -> ion | GUESSING | FAILS |

| F alb Supports F aeg -> ion | RESOLVED | SUCCEEDS |

| A tun -> gre | UNRESOLVED | - |

| F ion Convoys A tun -> gre | GUESSING | FAILS |

Now, things get different, because the resolve function is called for the Aegean Sea order, while that order is already in GUESSING state. The function will put this order in the dependency list (line 41 to 50) and return the stored guess resolution (line 51). The unwinding of the recursion will start at this point. While unwinding, the program will adjudicate according to the guess of the Aegean Sea and ignore the guesses of Ionian Sea and Greece.

The adjudicate function of the convoy order of the Ionian Sea will succeed based on the guess of the Aegean Sea. The resolve function of the Ionian Sea sees that adjudication result depends on a guess, because an order was added to the dependency list (condition on line 65 is false). It adds the convoy order to the dependency list, updates the resolution with the adjudication result, keeps the order in GUESSING state, and returns the adjudication result (line 83 to 91).

With further unwinding of the recursion, the adjudicate function of the support order of Greece gives a negative result (because it is cut by the successful convoy). This order is also added to the dependency list.

Finally, we are back at the Aegean Sea order. The administration is now as follows:

| Order | State | Resolution |

|---|---|---|

| F aeg -> ion | GUESSING | FAILS |

| F gre Supports F aeg -> ion | GUESSING | FAILS |

| F alb Supports F aeg -> ion | RESOLVED | SUCCEEDS |

| A tun -> gre | UNRESOLVED | - |

| F ion Convoys A tun -> gre | GUESSING | SUCCEEDS |

The recursion was executed as follows:

resolve(aeg)

adjudicate(aeg)

resolve(alb)

adjudicate(alb)

return SUCCEEDS (for adjudicate(alb))

return SUCCEEDS (for resolve(alb))

resolve(gre)

adjudicate(gre)

resolve(ion)

adjudicate(ion)

resolve(aeg)

return FAILS (for resolve(aeg))

return SUCCEEDS (for adjudicate(ion))

return SUCCEEDS (resolve(ion))

return FAILS (for adjudicate(gre))

return FAILS (for resolve(gre))

return SUCCEEDS (for adjudicate(aeg))

The adjudicate function of the Aegean Sea gives a positive result, despite the failure of the support from Greece. The resolve function will notice that the dependency list has been extended, but also that its own order is in the dependency list (condition on line 83 is false). So the adjudication result is based on the guess of its own order. Since the guess and the adjudication are different, this resolution is inconsistent.

The function will now restart the adjudication, but with a different guess. It sets all orders in the dependency list to UNRESOLVED. So the Aegean Sea, the Ionian Sea and Greece are all back in UNRESOLVED state, while Albania keeps its final RESOLVED state. The dependency list is also made empty (line 93 to 98).

The Aegean Sea is set to GUESSING, but now with a SUCCEEDS resolution (line 100 to 102). The adjudicate function is called for the second time for the Aegean Sea.

If the recursion is worked out in a similar way, the function will return again with a positive result, and the dependency list will contain the same orders.

Based on those two results, it can be concluded that there is only one consistent resolution for the Aegean Sea, and that is the successful move. The orders in the dependency list are again set back to the UNRESOLVED state (line 108 to 112), and the Aegean Sea gets its final state RESOLVED with the resolution SUCCEEDS (line 113 to 116). This result is also returned.

The adjudication of the whole will be completed by calling the resolve function for the other orders.

A few things additional things should be noted about the algorithm. When order x and y are in a cycle, the algorithm would not work properly if the following recursion could appear:

resolve(y)

adjudicate(y)

resolve(x)

adjudicate(x)

resolve(p)

adjudicate(p)

resolve(y)

resolve(q)

adjudicate(q)

resolve(y)

In the third call of resolve(y) the y order is already in the dependency list. When back in the resolve(q) function, no increase in the dependency list is observed (while still dependent on a guess). However, this dependency relationship is as in figure 14, and both x and y are part of a cycle with p and part of another cycle with q. Again, the algorithm is not designed to handle orders that are part of multiple cycles (which gives numerous complications), so this is not important.

However, when writing the adjudicate function, one should take care with this sensitivity for orders that are part of multiple cycles. Earlier, I gave the proof of theorem I — that orders can not be part of multiple cycles with the standard rules. However, in that proof I removed the dislodge rule (a support is cut when dislodged) from the support orders categorized as type E. The dislodge rule is only relevant for the type D supports, and those are the supports for moves where there is a unit attacking the support from the destination of the move. Since the proper working of the simple recursive guessing algorithm relies on the proof that orders are not part of multiple cycles, we should not re-introduce the dislodge rule for type E supports in the adjudicate function.

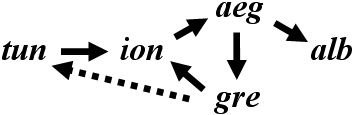

For instance, when we look at the dependency graph based on the situation of figure 16:

If the adjudicate(gre) calls resolve(tun) (to check whether it will dislodge Greece) then we get a dependency as shown by the dashed arrow in the figure. With the addition of this arrow, we have one cycle that includes Tunis and another cycle that excludes Tunis. The resolve function is not designed to handle such a dependency relationship. Thus, when programming the equations in the adjudicate function, one should take care not to check unnecessarily for supports cut by dislodgement, although the literal equations have specified such cuts without conditions.

With this in mind, we observe that to resolve the order of the Aegean Sea, the state of the Tunis convoy order remains untouched. At the same time we see that the order itself plays a major role in the situation. This shows again that a dependency on the existence of an order and the dependency of the resolution of an order are two different things.

The resolve function is not entirely fragile. If the adjudicate function calls the resolve function more than once for the same order, the function will handle it correctly. Suppose we have the situation as in figure 8, where Paris moves to Brest and Brest moves to the Mid-Atlantic Ocean. If we calculate adjudicate(par), we need to know the attack strength of Paris and the hold strength of Brest. When calculating this, for both strengths the result of resolve(bre) is necessary. We get a double dependency:

The resolve function is capable of handling this. One might also choose to prevent that the adjudicate function will call the resolve function twice for the same order. If written that way, the resolve function can be slightly simplified (but beware, there are multiple tricky situations).

Furthermore, the algorithm can handle a situation where a cycle is dependent on the resolution of another cycle. This cannot occur with the standard rules, but might happen with a variant rule. Suppose we have a dependency relationship as shown in figure 15. If the algorithm retreats from recursion and has added orders of the xyz cycle to the dependency list, then the adjudicate function may enter the branch containing the pqr cycle. The unfinished dependencies of the xyz cycle stay on the bottom of the dependency list, while the pqr cycle is solved at the top of the list. Once the pqr cycle is resolved, the algorithm will continue with the xyz cycle.

A final note should be made on the algorithm that determines the convoy path. The simplest way to implement this is to use a depth-first search algorithm with a recursive function. To do this, we have to mark the orders already visited in the search algorithm. We should be careful in taking global data for the marks, since in the search algorithm, the resolve function is called for the convoy orders. This in turn, may call the adjudicate function and lead to another convoy path calculation. It may even lead to the same convoy path calculation. If the resolve function is called for the Tunis order, then the path needs to be calculated; and to achieve this resolve(ion) is called. After some recursion steps, this leads to adjudicate(gre), which also needs to know whether there is a convoy path for Tunis.

There are several ways to avoid a mess-up of the global mark data for the convoy path search. One could make the mark data as local, by putting it on the stack. However, a real programmer who has also coded for small processors doesn't like to put arrays on the stack (an easy upper limit is 34 x 34 x 1 byte — that's a little bit more than 1 kilobyte, not really a problem). Another way is to assign the state variable UNRESOLVED, GUESSING or RESOLVED to the path equation also. This means that this equation is not only calculated in the adjudicate function, but it is also administrated by the resolve function. This complicates the data structures, because the nr parameter passed to the resolve and adjudicate functions may refer to a convoy path.

A simpler way is to call the resolve function for each matching convoy order first, and start the depth-first search algorithm afterwards. Since all the convoy orders are in the RESOLVED or GUESSING state during the execution of the depth-first search algorithm, this will prevent the depth-first search algorithm from being restarted in recursion.

Programming the simple recursive guess algorithm still requires that many details be coded correctly. Nevertheless, I believe this is the simplest flawless adjudication algorithm. The following properties can be observed:

- The equations are programmed only once,

- The generic resolve function is not very big,

- No complex data structures are required, and

- The generic part is nicely separated from the equation code.

And so, 10 years after I was first introduced to Diplomacy, finally, at last...

|

Lucas Kruijswijk (L.B.Kruijswijk@inter.nl.net) |