FOREWORD

You, gentle reader, have four choices in reading this article:

Trying to describe a mega-article like this is difficult. You could, I suppose, compare it to a Queen’s necklace, such as worn by Marie Antoinette (a good Austrian), or the meter-long pearl necklaces that the Tsars loved to give away to their Empresses or a newly wed Queen Wilhelmina in which each part is a precious jewel in itself. Or, perhaps more appropriately, you could compare it with a Sacher torte or Dobostorte, the famous seven-layer Hungarian dessert. But in essence my idea was simple: to take just another article about this or that in Diplomacy and combine it with others to create something memorable or infamous. How well I’ve succeeded is for you to judge.

INTRODUCTION

Some non-German speaking Dippers have a tendency, as do most non-Germans, to lump Austrians, Germans and German-speaking Swiss citizens together. That is a big mistake. In total they number about 100 million, of which the Austrians and Swiss each number about 8 million, with the rest being German. In fact, even dividing them into Austrians and German is a mistake. And beyond that dividing them into high and low Germans (e.g. Catholics and Protestants) and Austrians and Viennese is also a mistake. In today’s world the typical Viennese or Berliner will have more in common with each other than he will with a rural dweller of his own country. As you can see, it’s much more complicated than that, even for a Californian from a third of the world away. Of course we know both countries as they exist today have a long and divided history, interrupted by brief periods of unity, that has ebbed and flowed over the years, but that is what history is all about.

It might be wise to remember, as you read this story, that one of the great ironies in modern dip&Dip is the fact that the most famous German-speaking diplomat and Dipper is not a “real” German at all, but someone who escaped from Germany as a boy. What makes it doubly ironic is the fact that in the post-WWII period both Germany and Austria have produced many outstanding diplomats and Dippers. In fact, you could put together a first-class WDC event comprised of just players who were former German and Austrian presidents, chancellors or foreign ministers.

DIPLOMACY: THE GAME; THE ARTICLE THAT MIGHT HAVE BEEN

The boundary between A&G may be the quietest in Diplomacy, at least in the early stages of the game. There are at least three reasons for that:

- Each of them has better opportunities for gains elsewhere;

- Each of them has greater threats of losses elsewhere; and

- The five spaces that border n their common border are all land-locked.

They share no coastal or water spaces; which eliminates fleets as an element in their inter-action. Instead, what destabilizes their common border are two factors:

The unequal number of spaces between them: Austria has three: Tyrolia, Bohemia and Galicia; and Germany has two: Munich and Silesia; and

Only one of those spaces, Munich, is a supply center ; which offers an extra opportunity for gain or loss between the two.

And there, in one paragraph, you have a summary of all you need to know about A&G relations—all the rest is merely Peeriblah, although that hasn’t stopped scores of Diplomacy players and writers from writing about A&G.

Even a cursory examination of the hobby’s literature reveals that there are scores of articles: long and short, scholarly and frivolous l out there just waiting to be read. The Diplomacy-Archive.com has no less than 26 articles about Austria by authors like Richard Sharp, Don Turnbull, Manus Hand, Edi Birsan and, of course, Allan Calhamer. The same source has 27 articles about Germany; again by famous hobby writers like Stephen Agar, John Smythe, Edi Birsan and Brad Wilson. A search of past issues of Diplomacy World and The Diplomatic Pouch (both available online) reveals dozens of more possibilities. And, for the really curious a search on Google, Yahoo, etc. of subjects like “Austria Diplomacy strategy” will reveal not only articles about the game of Diplomacy, but even articles about the diplomacy of the real countries.

Perhaps it’s because of this plethora of articles about A&G or perhaps it’s because of the paucity of motivated writers in today’s hobby, but it was difficult to recruit others to contribute to this A&G article. I mention this not to throw stones but simply to point out a truth: it’s hard to get people to write, let alone think, in terms of more than 140 characters these days—the modern equivalent of the old Burma-Shave signs that I grew up with. And it’s not just in the hobby’s written literature. Think back to a recent DipCon or World DipCon game you played. When was the last time you got more than a “Grunt” or “Maybe” to your 30 second proposal for an alliance, strategy or tactical proposal before you or the other person rushed off for their next soundbite?

In prepping for this article I asked the Best Austria (David Johnson) and Best Germany (Christian Macdonald) at the 2014 WDC in Chapel Hill; and the Best Austria (Peter McNamara) and Best Germany (Dirk Bruggemann) at the 2014 EDC in Rome; as well as others; for their thoughts about their A&G wins. Only Dirk responded and you’ll find his effort in DW soon. In passing I also asked Moritz am Ende, Sven von Bargen, Holger Fiedler, Daniel Leinich, Andre Illevics, Frank Oschmiansky, Fabian Straub and Andreas Braun for a contribution. No response. I even asked Andrew Levy (Austria) and David Partridge (Germany) in my Youngstown IV variant Demo Game (Which you can follow in Diplomacy World.) for a few words. Again, no response.

However, sometimes patience and persistence pay off. In 1969 I wrote my first thesis, “From East, Alone, Toward Europe” about the Prague Spring in Czechoslovakia and the Warsaw Pact invasion of that country in August, 1968. My thesis caused quite an intellectual ruckus at my school because it contradicted the conventional wisdom of the day—that the Russians and their allies had intervened in Czechoslovakia for the purpose of crushing the Czech government. I suggested, on the other hand, that they had intervened to save the existing government in order to prevent an even more liberal government from taking power. What made my thesis so controversial was, as one of my profs put it, “This reads more like a James Bond story than an academic paper,” perhaps because I wrote it in the first person, actually writing about events I had observed or participated in; or perhaps because 99% of my source material came from newspapers and magazines, as well as personal observations. After all, there had been only one book on Czechoslovakia published in the United States since the end of WWII. Be that as it may, I survived and went on to other challenges. Some fifteen years later I came across a huge, scholarly work by a Canadian professor , H. Gordon Skilling, who specialized in Czechoslovakia. I laid out the $35 (A lot of money for a book in those days.) and spent nearly a year reading it. It wasn’t until I reached the end of the book that I realized Skilling had not only contradicted the conventional academic wisdom of his time, but had also vindicated my thesis.

Curious to know more I did some research and discovered that Skilling, after a long and distinguished career at the University of Toronto, had passed in 2001 at the age of 89. I did manage to track down Mark Kramer, one of Skilling’s pupils and a professor in his own right and director of Harvard University’s Cold War Studies program, and he was kind enough to share some knowledge about and insights into Skilling’s work and life. Closure was at hand.

I mention this because I’ve run into the same phenomenon in the hobby where I’ve discovered that sometimes it can take years and many different approaches to a subject before success is achieved. This article is an example of that.

At the same time I was chasing around the Diplomacy hobby looking for new articles about the game and play of A&G I became interested in the real world, real time relations of A&G. That interest led me down a more fruitful path as we will see.

I began by sending out a batch of emails to the foreign ministries of A&G, their respective embassies in each other’s country, and to various academic organizations in both. Then I sat back and waited to see what kind, if any, responses I would get. Within a few weeks I had replies from all of them. Sometimes it was a referral to a particular desk in the foreign ministry or at an embassy. Other times it was a polite “Go away and don’t bother us” response. Still, there were some interesting items and useful contacts that included: a long list of books and articles on Austrian foreign policy from a professor at the University of Vienna. The only problem was they were all in German; which I don’t read.

On the other hand, the new Hungarian ambassador , Reka Szemerkenyi, replied “Diplomacy is no translation software.”

One Austrian diplomat in Berlin described the relationship between Germany and Austria as follows: “The German-Austrian relations are good. They are characterized by the close proximity of the two rations, numerous cross-border family ties and personal encounters, common language and culture. The economic ties have numerous contacts with them and create closeness.”

However, an Austrian diplomat in Vienna described relations between the two countries thusly: “We Austrians always listen carefully to advice from our German cousins; and then go out and do precisely what we want.”

The truth, I suppose, is somewhere between the two.

As I suggested in my comments about source materials on A&G in the game Diplomacy so it is with real world, real time A&G. In addition to all the books and articles written about the relations of the two countries (Unfortunately most of them in German.) there are numerous articles available on line about the subject.

- http://german-foreign-policy.com, http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/foreign_relations_of_germany,

- http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/foreign_relations_of_austria,

- http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Austria_Germany_relations;

- http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/President_of_Austria;

- http://globalsolutions.org/blog/2015/02/Dictator_Diplomacy_Dilemma;

All these have useful sites.

Or you might try something as adventurous as a web search on “An examination of Austrian and German Diplomatic Relations since 1901.”

You might also see the following wki topics: Allied occupied Austria, Aftermath of WWII, Allied-occupied Germany, American food policy in occupied Germany, Soviet occupations and “The Third Man,” a movie set and filmed in post-WWII Vienna.

A NEW BOARD GAME EVOLVES: FROM THE HABSBURGS TO TODAY

What follows was the most challenging portion of this essay to write because it attempts to deal with time, spaces and personalities in a diplomatic context with the hope that as you read this you’ll think about them as they might relate to the game Diplomacy.

The game Diplomacy usually covers the period from winter 1900 until, unfortunately, the end of 1907; and more rarely these days until 1918 or so, by which time the game should have ended in a conclusive result. In this essay I begin with the Habsburgs of Maria Theresa and Franz Josef and go right up to tomorrow’s headlines.

Instead of the traditional game board spaces of Tyrolia, Bohemia, Galicia, Silesia and Munich we’ll be all over the place, from individual buildings in Vienna and Berlin, famous streets like the Unter den Linden and Ringstrasse to the new world of cyberspace and cyberwar.

After acknowledging the contributions of Austrians like Maria Theresa and Franz Josef; and Germans like Otto von Bismarck and his Kaiser; we’ll ponder what and how Adolf Hitler did what he did for A&G relations; before moving on to the post-World War II era and a series of fascinating people like Kurt Waldheim, Werner Frymann, Konrad Adenauer, Helmut Schmidt, Helmut Kohl, Richard von Weizsacker and Angela Merkel. From emperors and empresses to presidents and chancellors in less than a hundred years; it’s been a bumpy, but fascinating ride through history; and it isn’t over yet.

In the beginning were the emperors and empresses like Maria Theresa, Franz Josef and Wilhelm who, depending on their personalities and personal power, reigned as Autocrats or something less. In time they came to share their powers with advisors, at first usually a single chancellor or chief minister and later with a more involved and bureaucratic group of ministers. Over time the chancellors and ministers stayed and the emperors and autocrats gave way to dictators like Hitler, and eventually to the President/Chancellor/Minister of Interior system that exists today.

A word about that system. Most people assume that in A&G it is the Chancellor that has the most power and in some instances that is true. However, in Germany the President has a responsibility for moral leadership that can, at times, transcend the mere temporal power of a Chancellor. I’m thinking of German President Richard von Weizsacker’s address to the Bundestag in 1985 apologizing for Germany’s role in WWII. No Chancellor could have done that. On a more pragmatic note the President of Austria today is paid at the 15 5/6 level on the civil service scale. The Chancellor is paid at 15 and 4/6s and all other ministers are paid at 15 and 3/6s. The president leads. The chancellor governs. But what of the minister of the interior (e.g. chief cop) and why did I include him or her (as it is in Austria currently)? In point of fact the minister of the interior is the third leg in the triumvirate that runs A&G. Although not as well known internationally as a president or chancellor the minister of the interior is usually well-known at home and often has far-ranging delegated powers even if they are not being exercised. A good metaphor for the power balance can be seen in the real estate these three powers hold in Austria.

The heart of Vienna is the Ringstrasse which the Emperor Franz Josef created at about the same time the United States was engaged in its Civil War. Josef wanted a street to celebrate Austria’s wealth, power and beauty. Adjacent to the Ringstrasse was the Hofburg Palace complex, the center of Habsburg power. At one corner of the Hofburg was the Ballhausplatz (“Ball house square,” named for the former tennis court that once stood there. Today, looking across at each other are two buildings, one addressed at Ballhausplatz 2 has been the official home of the Austrian chancellor for over two hundred years. It was in Ballhausplatz 2 that von Metternich hosted the Congress of Vienna after Napoleon’s defeat in 1814 that resulted in the “balance of power” that would inspire Calhamer’s game Diplomacy. One cannot help but wonder if Henry Kissinger, who made his reputation with his thesis on Metternich and the Congress of Vienna, has ever walked the rooms of Ballhausplatz 2? It was also in Ballhausplatz 2 where , in 1934, the Austrian chancellor Dollfuss was murdered by the Nazis, and the last chancellor of a Free Austria, Schuschnigg, gave his “farewell address” in 1938. Across the street Ballhausplatz 1 has been the office of the Austrian president for some years, although the president’s actual office is elsewhere in the Hofburg. Interestingly, the first floor of the president’s office building houses the largest wine cellar of any world leader. But, perhaps more important is a third building adjacent to the same square that doesn’t get much notice. It’s the former Palais Modena that belonged to the Modena, Italy Habsburgs. The relatively modest building and the large, modern office building behind it are connected by underground tunnels to Ballhausplatz 2 and 1, as well as a nearby church. The Palais Modena is the home office of the Minister of the Interior. For the record, the headquarters of the Austrian Foreign Ministry is located a block or so away at Minoritenplatz 8.

The Ringstrasse or “World’s most beautiful boulevard” as the Austrians like to say, is celebrating its 150th birthday this year with a lot of special exhibits and programs. One of the more interesting is at the Vienna Museum of Architecture and is called “Vienna: Pearl of the Reich, Planning for Hitler,” an exhibition that challenges Austria’s long history of claiming victimhood and denying its collaboration with the Third Reich.

I remember asking Eric Adenstedt in 1989 where Austrian Dippers congregated. With a grin he took me to the Vienna International Centre (VIC), a huge, modern office complex and conference center that is the Vienna headquarters of the United Nations. It was built between 1973 and 1979 at the suggestion of the then Austrian Chancellor Bruno Kreisky. Six Y-shaped office towers surround a conference building with a total of 2,480,000 square feet. The highest tower is 28 stories high. Five thousand people work in the VIC, half of them for UN agencies that deal with nuclear-test-bans, the International Atomic Energy Agency, the UN Commission on International Trade Law, the UN Industrial Development Organization, the UN Office on Drugs and Crime, the UN High Commissioner for Refugees, the UN Office for Outer Space Affairs and, fittingly, the International Commission for the Protection of the Danube River The other half of the VICs workers mostly work at the tax-free, duty-free commissary located in the VIC (Which is an extraterritorial area, exempt from the jurisdiction of local law—including the notoriously high Austrian liquor taxes.). Foreign workers and diplomats can pretty much buy what they want without paying taxes. Austrians are charged the going rate.

Determined to out-shine his Austrian rival Kaiser Wilhelm ordered the construction of his own “Ringstrasse,” called the Unter den Linden which in time became the center of Berlin and the Prussian empire. Hitler, in an effort to reshape Berlin into a Nazi powerhouse, constructed his own monuments: chief among them the new Chancery, complete with a 4,000 square foot office for the Chancellor. Still, we know that Hitler also had a home in Munich at Prinzregentenplatz from 1929 – 1945. The third floor apartment consisted of nine rooms in two combined apartments in a relatively modest residential building on a plaza. It was there that he met with Mussolini while trying to get his approval for the German annexation of Austria, something Mussolini strongly opposed. It was in the same apartment that Hitler met with Chamberlain after their famous Munich meeting. Today the apartment is part of the local police station. Not as well-known is the fact that Hitler had a private pied a terre a block from the Chancery in Berlin where he often stayed in the early days of the Third Reich. Surprisingly, Hitler’s only security there came from a single policeman on guard outside. Then came WWII and thirty-years of a divided Berlin and Germany. With the re-unification of Berlin and Germany a new center of power has been built on and around the Unter den Linden.

The old Reichstag was given a cosmetic face-lift. A huge new chancery was built at a cost of $600M including a top floor penthouse for the Chancellor (The current chancellor, Angela Merkel, continues to own and use the same apartment she and her husband have owned for years.), a giant new American embassy was built around the corner from it, and even the old Hotel Adlon was restored to its past glory and priced accordingly. But space on the Unter den Linden was running out, so the government determined to build a new, modern government center for a new, modern and rich Germany as it began to expand the center of power. A modern new Ministry of the Interior building went up, covered with the same glass façade as the new Reichstag to show the world that Germany had become more transparent. Most recently, on the nearby Chausseestrasse a giant new headquarters for the BND (The German equivalent of the US NSA) was built at a cost of $1B, an amount equal to a year’s budget for the entire BNA. A look at the BND website reveals that the new building covers an area equal to 35 soccer fields, has 5,200 rooms, 3,300 offices, 4,000 workplaces, 14,000 windows, 12,000 doors, underground parking for only 600 cars, and required 20,000 tons of steel to build. The web site doesn’t mention that the cost of the building was about equal to what Hitler’s chancery cost in today’s dollars, and the footprint of the main buildings were about the same.

But in the new Germany things can go wrong, as we shall see. Even before it was finished it was revealed that a complete set of the blueprints of the building, including the locations of security systems, had disappeared. Then, even as the first 150 of some 4,000 workers, began to move into the building a series of leaks, promptly dubbed Watergate by the German press, in the building’s pipes flooded offices and ruined some of the 1,800 computers in the building.

|

|

|

|

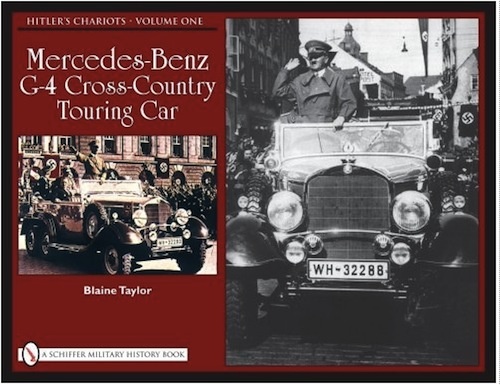

Having seen and written about some of the spaces and places were the leaders of A&G work and live let’s move on; quite literally. Maria Theresa, Franz Josef and Wilhelm moved around mostly in carriages, trains, yachts and some of the earliest automobiles. Franz Josef’s first car was a Daimler designed by Porsche. Hitler favored a 12 cylinder, Mercedes Benz touring car and an early model of the Volkswagen “bug,” both driven by chauffeurs of course. Today the president of Germany has a Mercedes Benz and the chancellor has an official Audi, although Angela Merkel has been seen driving her personal auto, a Golf, at home. The president and chancellor of Austria both favor Mercedes Benz. And for those longer trips all have access to a variety of VIP aircraft including the most modern Airbus jets.

ESPIONAGE AND PROPAGANDA IN TODAY’S REAL WORLD DIPLOMACY

Henry L. Stimson, US Secretary of War, infamously said, “Gentlemen don’t read each other’s mail” when he ordered the “black chamber” abolished and an end to US spying; and the debate was on—never more so than today when Eric Snowden’s “leaks of classified documents” has caused an uproar in the worldwide intelligence community. Looking back at Burt’s discussion of espionage and propaganda, I’m tempted to change Stimson’s quotation to “Diplomacy players don’t read each other’s orders. Says who?”

You can find a lot of articles and quotes online about Espionage, Spying, Treason, Propaganda, Disinformation, etc. Goodreads has 73 quotes about Espionage and 168 about Propaganda. BrainyQuote has fewer quotes but they are of a higher quality I think.

With this historical background and our stage set across today’s A&G, let’s now move to a story that is still in the news. I am, of course, referring to the reports that the BND has been accused of spying itself, after Germany indignantly protested its leaders were being spied on by the NSA—only this time the shoe was on the other foot and it was the BND that had been accused by the Austrian Minister of the Interior of spying on the leaders of Austria!

The headlines came fast and furious from the Austrian and Germany and gradually spread around the world as the international media couldn’t resist such a juicy story.

- “Scandal over spying shakes German government.”

- “German spying prompts Austrian complaint.”

- “Austria files legal complaint over German espionage.”

- “Austria files complaint after reported German espionage.”

- “Austria files legal complaint over German-U.S. spying suspicions.”

- “Austrian chancellor says Merkel’s economic policy too timid.”

- “Lawmakers in France move to vastly expand surveillance.”

- “Merkel Ducks Putin’s Victory Parade.”

- “Another spying scandal adds to political crisis for Merkel.”

- “Fiercely critical of NSA, Germany now answering for its own spy practices.”

With the number of countries involved, the importance of the players, the sensitivity of the issues and the size of the stakes; this is not a tempest in a teapot. It’s a debate that will be with us for a long, long time. In the near-term the battle will be between the various opposition parties trying to use the crisis to stir up trouble and the in power parties that will try to sweep it under the carpet so business (e.g. spying) can continue as usual.

As this drama plays out let’s keep an eye on six of the principals involved: the two presidents, Heinz Fischer of Austria since 2004 and Joachim Gauck of Germany since 2012 will probably stay out of the controversy; the two chancellors, Werner Faymann of Austria since 2008 and Angela Merkel of Germany since 2005 will deal with the consequences in the parliament; but the real intriguing diplomacy may go on at the foreign ministry level. Germany’s Foreign Minister since 2013 is Frank-Walter Steinmeier, a professional political bureaucrat who has served in key positions since 1998. Among them were terms as Secretary of State in the Federal Chancellery and Commissioner for the Intelligence Services, Head of the Federal Chancellery, Minister of Foreign Affairs (twice), Vice-Chancellor and chairman of the SPD parliamentary group. Austria’s Foreign Minister since 2013 is Sebastian Kurz, who, at 27, is Europe’s youngest foreign minister with no previous experience in the field. His response to his appointment was, “It’s true, of course. Due to my age I have limited experience and of course hardly any diplomatic experience. But what I bring is lots of diligence, energy and the desire to contribute something.” It should be interesting.

CONCLUSION

It seems ironic that just a few days ago I was writing an article about “The Greatest Diplomacy Game Ever!!!” and extolling the virtues of Angela Merkel as Chancellor Germany and diplomate extraordinaire; and now I’m writing a story that prominently mentions her current difficulties because of the BND spying scandal in Germany. But that’s the way it is in diplomacy and, I suspect, it’s just the same in Diplomacy. Your thoughts?

AFTERWORD

As I sat nearly by myself in a first class rail car on the way back to Bruxelles from Bonn I had to pinch myself to remind me that I had just spent a pleasant two hours with the President of the Federal Republic of Germany, Richard von Weizsacker; a meeting that came about because I had taken the time to write him a note thanking him for his speech to the Bundestag some four years earlier in which he apologized for Germany’s role in WWII. I don’t even remember what I wrote in that note but it must have left an impression on somebody because when I asked to interview him four years later I got a speedy positive response. Mostly we talked about his speech and what was happening in Germany as we met. He seemed very curious about the reaction to Germany’s current events among America’s young people. As I thought about it I realized that for one of a handful of times in my life I had just spent some time with a truly great and remarkable man.

Just a month later I was sitting on a British Airways jet on a flight to London from Vienna where I had just spent an amazing three weeks. One of the highlights of that trip was an opportunity to meet with Kurt Josef Waldheim who had served as Secretary-General of the United Nations from 1972 to 1981, and was then serving as the ninth President of Austria from 1986 to 1992. After stories about his service in WWII began to circulate Waldheim had become persona non grata with other world leaders and was living in virtual exile at home in Ballhausplatz 1. No other leaders wanted to be seen with him or even talk to him. I really hadn’t expected to be granted an interview with him but perhaps because I had met with von Weizsacker or because I had promised not to ask any questions about his Nazi past I was told to present myself at his office on a particular day at a particular time. I was told no recording devices or pictures would be allowed, that the interview would last 30 minutes and he would use an interpreter, although I knew perfectly well that he spoke excellent English. Still, it was an opportunity not to be missed. His office was not large but decorated in that white, red and gold décor the Austrians love. He was alone except for one aide and a translator. He sat there in a dark blue suit in one of those gilded chairs that always look like they’re going to collapse at any moment. He looked very old and very alone. After a half-dozen innocuous questions and equally innocuous replies I noticed his aide beginning to look at his watch and I knew my time was up. However, I had mentioned that I just seen four operas at the Statsopera and the Volksopera in two days and that seemed to get his interest. We spent another fifteen minutes discussing opera. Then he paused and looked at me. Before the aide could show me out I decided to go for broke and asked Waldheim if I could ask a question about his service at the United Nations. He hesitated and then said yes. I guess I blind-sided him with my question and his eyes started to widen even before the translation was finished. I had asked him, in so many words, “During your service at the United Nations did any of the delegations attempt to influence your actions because of your past?” Without responding he looked at his aide, who practically jumped in front of me, and said, “The interview is over,” and headed for the door. Waldheim stood up, but didn’t offer his hand, so I turned and left without an answer to my question. His lack of a response was all the answer I needed. As I thought about his on the plane I realized that once again I had been in the presence of a truly not-so-great but equally remarkable man.

|

Larry Peery (peery@ix.netcom.com) |

If you wish to e-mail feedback on this article to the author, and clicking on the envelope above does not work for you, feel free to use the "Dear DP..." mail interface.